Researchers from the University of Minnesota developed an immunotoxin to target B-cell tumors. The study entitled “Phase I Study of a Bispecific Ligand-Directed Toxin Targeting CD22 and CD19 (DT2219) for Refractory B-cell Malignancies” was published in Clinical Cancer Research by University of Minnesota researchers.

Researchers from the University of Minnesota developed an immunotoxin to target B-cell tumors. The study entitled “Phase I Study of a Bispecific Ligand-Directed Toxin Targeting CD22 and CD19 (DT2219) for Refractory B-cell Malignancies” was published in Clinical Cancer Research by University of Minnesota researchers.

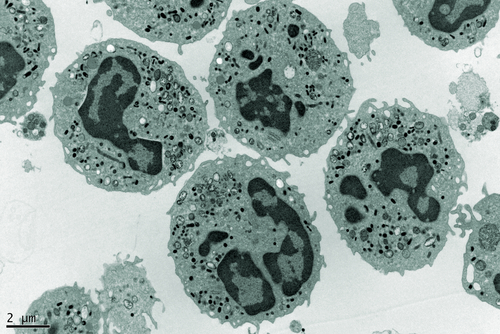

B-cell malignancies are a heterogeneous group of disorders with widely diverse characteristics and clinical behavior. Although there have been improvements in survival for patients with B cells tumors, the majority of patients continue to relapse following standard chemo-immunotherapy. In the United States more than 15,000 patients die per year from B-cell cancers.

Study author Dr. Vallera said in a news release that the majority of patients with B-cell tumors have two typical “fingerprints” on the surface of leukemia and lymphoma cancers, called CD22 and CD19, both transmembrane proteins of crucial importance for B-cell function.

The research team chose two antibody fragments targeting human CD19 and CD22 and attached these two antibodies to a powerful toxin, the bacterial diphtheria toxin, through genetic engineering. The genetically engineered immunotoxin, designated DT2219, can bind to the two targets on tumor cells, eventually leading to its death.

The team performed a phase I dose-dependent study to evaluate the safety, maximum tolerated dose, and preliminary efficacy of DT2219 in 25 patients with relapsed/refractory B-cell lymphoma or leukemia. The enrolled patients had chemo-refractory pre-B acute lymphoblastic leukemia, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, or non-Hodgkin lymphoma and had received a total of 2 to 5 previous treatments. Furthermore, 8 patients had received previous unsuccessful bone marrow transplants. All tumors were positive for CD19 and/or CD22 and patients were treated with a single cycle of increasing doses of the immunotoxin therapy. DT2219 was administered intravenously during 2 hours every 2 days in a total of 4 doses.

The results showed that 2 of the 10 patients had long-lasting responses, and in one patient the signs and symptoms of the disease disappeared completely, after receiving two cycles of therapy. Clinical responses occurred between the doses 40 to 80 µg/kg administered in four infusions.

Dr. Vallera said the team will perform a phase II trial assessing an increased number of therapeutic cycles, hopefully increasing response rates. Surprisingly, the drug was sufficiently effective to completely eliminate cancer in one of their patients. Moreover, antibodies against the bacterial toxin (resulting in drug rejection) did not occur in 70% of patients, with the team currently developing a less immunogenic form of the toxin for the next-generation drug.

Dr. Vallera highlighted that “Another important fact about our drug is that it was home-grown, meaning there was no commercial partner, which is rare.” He added that this immunotoxin was almost completely supported by private donations including individuals that have lost loved ones to cancer.