A new study revealed patrolling monocytes, a subtype of white blood cells, directly control tumor metastasis to the lung in a living mouse model of cancer, a finding that could lead to new immunotherapies to treat the lethal disease. The study entitled “Patrolling Monocytes Control Tumor Metastasis to the Lung” was published in Science by La Jolla Institute for Allergy & Immunology researchers.

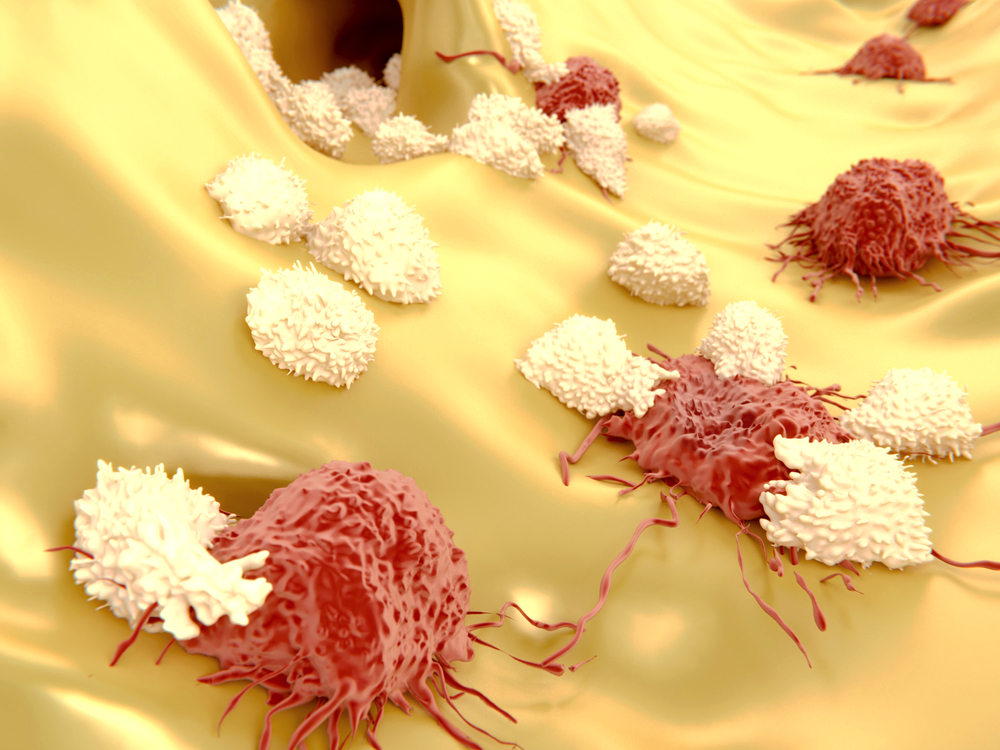

The immune system plays a crucial role in tumor growth and metastasis. Among the many cells on the immune front line are patrolling monocytes, whose job is to cruise the bloodstream, cart off cellular debris, and block invasion of a less benign population of inflammatory cells. “Our study shows that this subgroup of white blood cell is a key player in orchestrating the killing of metastasizing tumor cells,” Catherine C. Hedrick, PhD, from the Division of Inflammation Biology and senior author of the study, explained in a press release.

In this study, the research team showed that patrolling monocytes enriched the microvasculature of the lung, decreasing tumor metastasis in several metastatic tumor mouse models. The team injected tagged melanoma cells into the bloodstream of either normal or mice deficient for a specific gene (Nr4a1) that does not allow them to develop patrolling monocytes, registering the migration of cancer cells. After 24 hours, there were more melanoma cells in lung blood vessels of deficient mice than in normal mice, suggesting that in the absence of patrolling monocytes, animals are more susceptible to lung metastasis. Additionally, the researchers followed patrolling monocytes in the lung vasculature, filming them pursuing invading cancer cells to demonstrate their efficacy. “These cells recognize and could help destroy early metastasizing tumor cells in the blood, even before they can invade new tissues and form new tumors,” said Professor Hedrick.

Surprisingly, when researchers transferred protective monocytes into mice after the injection of cancer cells, protection against tumor metastasis failed. This meant that patrolling monocytes had to be in the microvasculature before metastatic tumors cells arrived to prevent them from breaching the vessel wall. Thus, the protective effect of patrolling monocytes was not successful after tumoral invasion. But what is called a “rescue” experiment — adding patrolling monocytes into mice that lacked them before injecting cancer cells — they found inhibited cancer cell migration into lung vasculature. “The fact that you can add these cells back into a mouse that lacks them and observe reduced metastasis shows that they are key factors in suppressing lung metastasis,” said study author Richard Hanna, PhD.

Dr. Hanna stressed this study does not prove that patrolling monocytes directly kill tumor cells, but that they favor the recruitment of other immune cells, natural killer cells, able to kill cancer cells. “Alternatively, these monocytes could scavenge tumor cell debris, which might dampen the inflammatory response,” Hanna added.

“Lung metastasis is 85% lethal within 5 years with currently no good treatment options,” said Hanna. He highlighted their study demonstrated that immunotherapy approaches against tumor metastasis should be complemented by strategies that may increase the number or activity of patrolling monocytes, either by using pharmaceuticals or by transferring cells into a patient. “Patrolling monocytes may prevent metastasis to other organs as well, a possibility that we will consider in future studies,” concluded Professor Hedrick.