In a new study entitled “Epigenetic silencing of TH1-type chemokines shapes tumour immunity and immunotherapy” researchers at the University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center discovered a new mechanism by which tumors shield themselves from attack by the immune system, thereby impairing the efficacy of immunotherapies. They found that epigenetic marks in tumor cells, specifically DNA methylation, repress the expression of key cytokines that direct immune T cells toward the tumor microenvironment. Combining epigenetic drugs with immunotherapy improves therapeutic action in tumor-bearing mice. The study was published in the journal Nature.

In this study, researchers hypothesized that genes important for alerting and directing immune responses against tumors are silenced by epigenetic mechanisms — factors that bind DNA sequences and are capable of switching genes on and off without changing the DNA sequence.

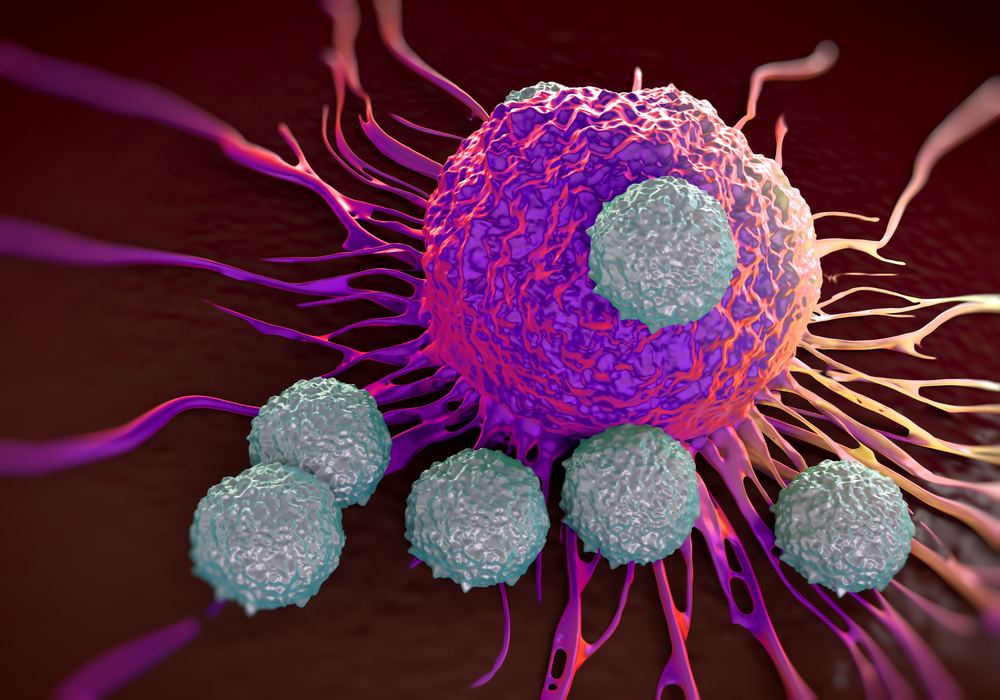

The team used human ovarian cancers as its model and discovered that methylation (an epigenetic mark) in tumors repressed the production of two specific chemokines, CXCL9 and CXCL10, therefore preventing T cell trafficking into the tumor and shielding tumor cells from immune responses. Accordingly, the team discovered that the presence of this epigenetic mark is associated with fewer tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells, and therefore a worse disease prognosis. When the team used epigenetic modulators to treat tumor cells, removing the repressive marks, they observed an increase in tumor T cell infiltration and a consequent decrease in tumor progression. Most importantly, combining cancer immunotherapies (such as programmed death-ligand 1, PD-L1 or adoptive T-cell transfusion) with epigenetic modulators enhanced therapy efficacy.

These results highlight a novel mechanism of tumor immune-evasion and suggest that selective therapeutics inducing an epigenetic reprogramming can restore T cells’ anti-tumor dynamics and foster the efficacy of cancer therapy. Weiping Zou, M.D., Ph.D., Charles B. de Nancrede Professor of Surgery, Immunology and Biology at the University of Michigan Medical School and study lead author said of these findings in a press release: “We defined a molecular mechanism to explain why some tumors are inflamed and others are not — and consequently why some patients will be responsive to therapy and others not. If we can reprogram this epigenetic mechanism, then the therapy might work for more patients.”