Researchers may have taken a possibly important step in advancing cancer immunotherapy by successfully altering pro-tumor immune cells to become tumor-fighting immune cells. Their paper, titled “A Breakthrough: Macrophage-Directed Cancer Immunotherapy,” was published in Cancer Research.

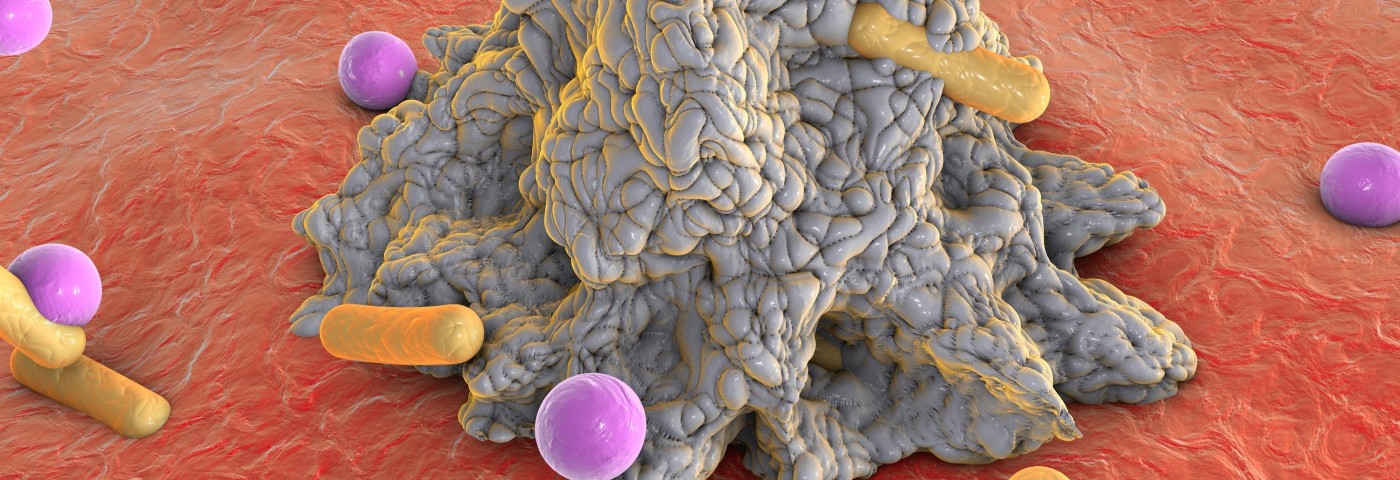

Macrophages are white blood cells that engulf invading microbes, cancer cells and cell debris, in a process called phagocytosis. These cells also play a vital role in innate (non-specific) immunity and in the recruitment of other immune cells. Macrophages can differentiate into two types, M1 macrophages (“kill-type” phenotype), which encourage inflammation and have been associated with anti-tumor activity, and M2 macrophages (“repair-type” phenotype), which encourage tissue repair and have been found to promote tumor-growth.

Previous research has consistently pointed to the importance of macrophages and their sub-types in the growth or regression of tumors, and to the M1/M2 ratio as a measure of cancer susceptibility. In fact, an M1/M2 macrophage ratio that favors an abundance of “kill-type” macrophages is associated with a lower likelihood of developing cancer. In mouse models, modulating a high M1 to M2 ratio has been shown to slow or stop cancer. The anti-cancer effects of the M1 macrophages resides in their ability to kill cancer cells, and to stimulate Th1-type cytotoxic T cells and other killer cells, which recognize and attack tumors.

The study described a method of tipping the scale in favor of a dominant M1 macrophage population, essentially by replacing the macrophage population as it naturally dies with a population dominated by the M1 sub-type. This is accomplished by exposing the macrophages to cytokine interferon gamma, which favors the M1 phenotype. Because this cytokine has numerous effects and mediates several processes, however, its use as a therapeutic agent is somewhat problematic. Researchers suggested getting around this by increasing the macrophages’ sensitivity to interferon gamma already existing in the body, and by increasing interferon gamma only in tumor tissue to keep its effects localized.

“The immune system’s killer cells produce interferon gamma and one promising strategy is to get them to the tumor and activated in the right way. Cytotoxic T cells can directly kill tumor cells. But they also produce interferon gamma. Both are likely contributing to the anti-tumor effect. By devising approaches to tune macrophages in the right way, we hope to further improve immunotherapies,” Dr. Laurel Lenz, an investigator at the University of Colorado Cancer Center and a study author, said in a press release.