In what is being deemed as an historic scientific breakthrough, researchers have identified thousands of previously unknown immune signals that may have implications in autoimmune diseases, immunotherapy, and vaccine development.

The findings included in the study “A large fraction of HLA class I ligands are proteasome-generated spliced peptides,” published in Science, are seen as the biological equivalent of discovering a new continent.

“It’s as if a geographer would tell you they had discovered a new continent, or an astronomer would say they had found a new planet in the solar system,” the study’s co-author, Prof. Michael Stumpf from the Department of Life Sciences at Imperial College London, said in a press release. “And just as with those discoveries, we have a lot of exploring to do.”

The research was led by Juliane Liepe, PhD, Imperial College London, and Michele Mishto, PhD, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, in collaboration with Utrecht University in the Netherlands and LaJolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology in California.

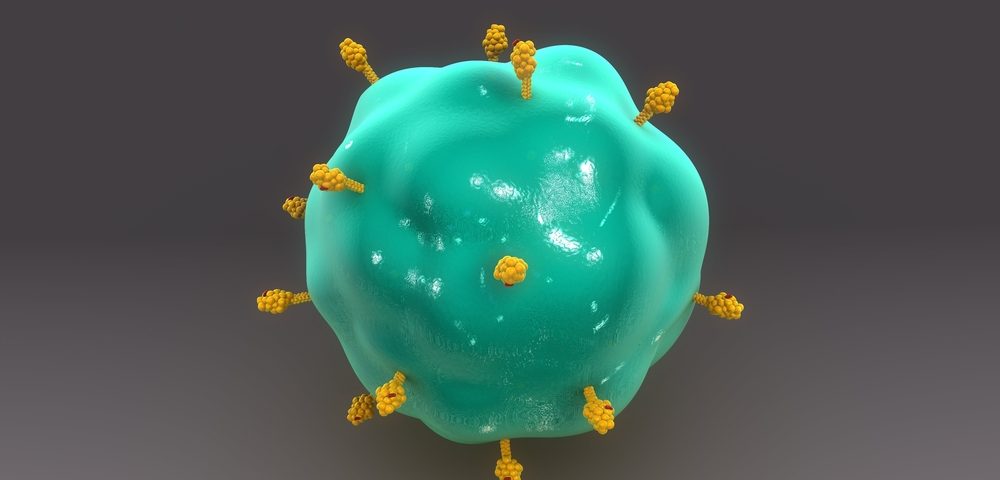

Antigen-presenting cells such as macrophages and dendritic cells often start the immune response by engulfing proteins from human bodies or foreign bodies like viruses and bacteria, degrading their proteins into small peptides and presenting them at their cell surface to be scanned for T-cells. When T-cells find one of the small peptides (epitopes) at the surface of antigen-presenting cells, all the cells or pathogens presenting the epitopes are then recognized as foreign and destroyed by T-cells.

Previously, researchers believed that proteins from the foreign bodies were cleaved in a sequential manner to create the epitopes, which were then presented at the surface of antigen-presenting cells in order. But the recent study shows that more than one-third of all the epitopes presented by the immune cells are spliced epitopes. Those epitopes are composed of two fragments from different positions in the protein that stick together out of order, creating a new sequence.

Spliced epitopes had been described in the past but were thought to be rare. Using the new development that enables the mapping of cell surfaces, the researchers found that the spliced pool of epitopes accounts for about one-third of the entire immune signals in terms of diversity and for about one-fourth in terms of abundance.

The new findings can help researchers understand many autoimmune diseases, and identify new targets for vaccines or immunotherapy.

The researchers believe that the extra epitopes give the immune system more to scan and more possibilities of detecting disease, but spliced epitopes may eventually overlap with the sequences of proteins from healthy cells, which start being recognized as harmful. This attacking of normal tissues may lead to the development of diseases like Type 1 diabetes or multiple sclerosis.

“The discovery of the importance of spliced peptides could present pros and cons when researching the immune system,” Liepe said. “For example, the discovery could influence new immunotherapies and vaccines by providing new target epitopes for boosting the immune system, but it also means we need to screen for many more epitopes when designing personalized medicine approaches.”