Immune checkpoint blocking drugs do not trigger long-term changes in T-cells, which become confined to their inactive state by epigenetic changes. This likely explains, at least in part, why cancer treatment with checkpoint blockers usually fails to produce long-lasting effects.

The findings surfaced in two articles published in the latest issue of the journal Science: “Epigenetic stability of exhausted T cells limits durability of re-invigoration by PD-1 blockade,” and “The epigenetic landscape of T cell exhaustion.”

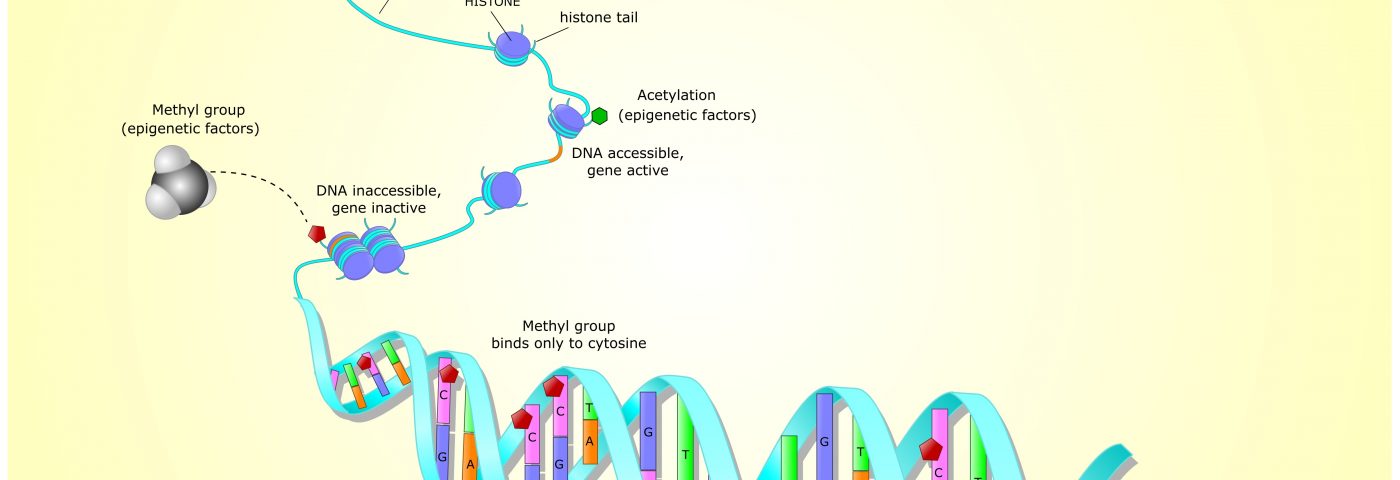

Epigenetics is a way for the body to control which genes in a cell are turned on. Since all the cells in the body share the same DNA, the mechanism allows cells to use only certain sets of genes at any given time. The activity of a set of genes is what makes it possible for the body to form various cells and organs, or, as the authors of the first study put it, it’s “the reason a liver cell stays a liver cell and doesn’t become a lung cell.”

Checkpoint inhibitors make use of the fact that cancers, as well as chronic infections, hijack an immune safety system. Immune checkpoints exist to protect systems from exaggerated immune responses and autoimmunity, but as a cancer takes over, immune T-cells get “exhausted,” as researchers say — they become unable to respond to immune stimuli.

Checkpoint blocking drugs remove this restraint, but until now, it has been uncertain whether blocking the checkpoints allows cells to truly return to their former state. It became clear that it does not.

In the first Science study, a research team from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania kept track of changes in T-cells after they had been exposed to PD-L1 blockade. They discovered that very few memory T-cells were formed, and so no long-lasting effects could develop, particularly if the antigens remained that had inactivated the cells in the first place.

Further analyses revealed why the drug treatment failed to produce long-lasting changes. Exhausted T-cells had an epigenetic profile that differed from memory cells or other types of T-cells.

“What these new findings on exhausted T cells tells us is that the unique epigenetic profile of exhausted T-cells causes these cells to express a different overall set of genes compared to memory or effector T cells,” E. John Wherry, PhD, director of the Institute for Immunology at Penn and the senior author of the study, said in a news release.

And, unlike the team’s expectations, the epigenetic profile did not change much after checkpoint treatment. “We predicted that exhausted T-cells would not have a distinct epigenetic profile but have the molecular flexibility to obtain immune memory,” said Wherry, who is also the Barbara and Richard Schiffrin President’s distinguished professor of microbiology at the Perelman School of Medicine. “But we found that exhausted T-cells are quite set in their ways.”

The findings suggest that the cells had become a distinct type of T-cells, and not only T-cells restrained by checkpoint signaling.

According to Kristen Pauken, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher in the Wherry lab and the study’s first author, this inflexibility may limit current immunotherapies using checkpoint blockade.

The remarkably different epigenetic profile of suppressed T-cells was confirmed in the second Science study, led by Nick Haining, MD, from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in collaboration with the Penn researchers.

The study found that exhausted T-cells in both humans and mice have a very specific epigenetic profile. The study was able to link some of the features of the immune exhaustion to the epigenetic changes they observed.

The two studies now point toward the combination of immune checkpoint inhibitors with drugs that revert such epigenetic changes, allowing exhausted T-cells to be reprogrammed back into functional and long-lasting memory T-cells.