Researchers have developed an artificial membrane that, similar to antigen-presenting cells, can trigger the activation of T-cells toward a particular target.

The technique, which might be used not only as a future cancer immunotherapy but also to provide additional insight on how T-cells are activated, was recently presented at the Joint Congress of the British and Dutch Societies for Immunology Dec. 6-9 in Liverpool, England.

Our immune system works in a very coordinated fashion, and cells are usually recruited to infection and activated in a sequential manner. The first cells to arrive at an infection site are usually cells that engulf the foreign pathogens, like neutrophils and macrophages, which usually make up the body’s first line of defense.

But if these cells cannot eliminate a threat, such as a pathogen or cancer cells, they are also able to recruit and activate more specific cells, like T-cells. Indeed, these cells, which are called antigen-presenting cells (APC), can “present” proteins from the tumor cells, telling the immune T-cells that they should react against cells which carry such proteins.

Researchers have tried to use natural APCs as an immunotherapy, but the procedure is costly and time consuming and has shown variable results. To address that problem, PhD student Loek Eggermont and a team from the Figdor lab at Radboud University Medical Centre in the Netherlands developed an artificial antigen-presenting cell instead.

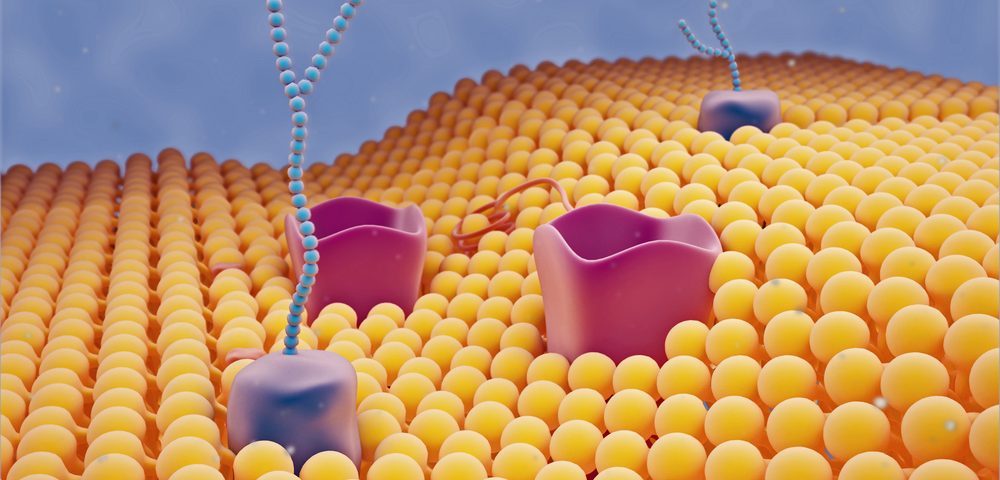

They developed a scaffold with a nanoworm-like structure that mimics the cell membrane of APCs, with several T-cell activating proteins embedded in it. This artificial structure, they found, was able to activate human T-cells, influencing their proliferation and differentiation, much like normal APCs do.

In addition, the researchers found that to achieve optimal activation of the T-cells, there were certain receptors on T-cells that had to be activated in close proximity, suggesting that the place where the proteins are located in the artificial APCs will influence T-cell activity.

This new method will now provide researchers new tools to further understand the mechanisms behind T-cell activation.

The team is now hoping to create a polymer that is more specific to cancer cells so that it will tell T-cells to attack them. This polymer will then be tested in mice to assess whether it may be useful to treat cancer patients in the future.

“We have shown that an artificial antigen-presenting cell can be effective in activating T-cells in in vitro studies,” Eggermont said in a press release. “Our findings also help us to better understand the mechanisms behind this T-cell activation. Although more studies are now needed to see if this system works in animal models, we hope that it might one day lead towards development of new off-the-shelf cancer immunotherapies.”