Cancer patients with higher amounts of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) in their spleens are more likely to die, according to researchers at the University of Colorado Denver Anschutz Medical Campus.

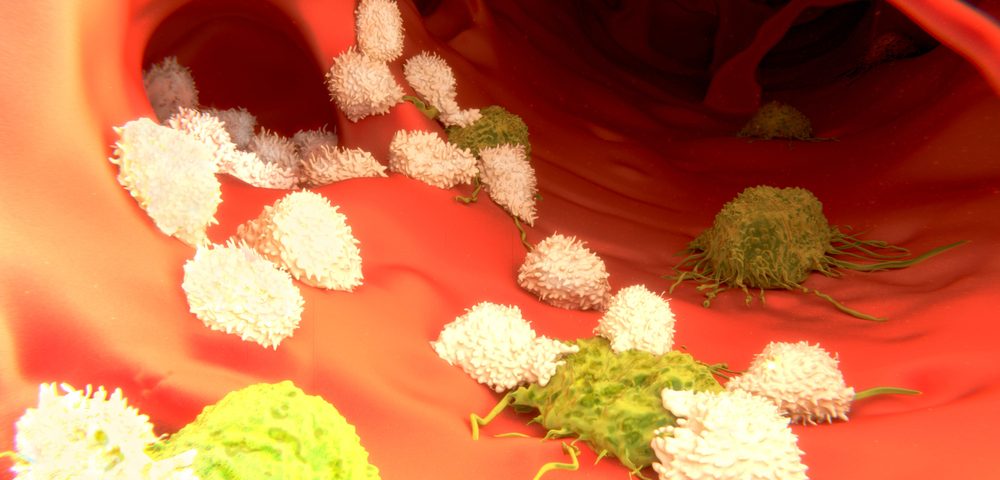

The team has shown for the first time that human cancers work very similarly to what has been described in mice models, with MDSCs preventing T-cell proliferation and activation, and tamping down anti-tumor immune responses.

But the study, “Immunosuppressive myeloid-derived suppressor cells are increased in splenocytes from cancer patients,” published in Cancer Immunology and Immunotherapy, also reveals fundamental differences between mice and humans.

“I would estimate that the majority of basic immunology has been worked out in mice, specifically in the spleens of mice, because they offer ready access to large numbers of lymphocytes or splenocytes [immune cells in the spleen]. Many versions of vaccines and tumor models rely on the responses of these mouse splenocytes. But it turns out we don’t know as much about human splenocytes and their immunologic importance. There’s a big leap of faith that mouse models are applicable to humans,” Martin McCarter, MD, investigator at the University of Colorado Cancer Center and surgical oncologist at the University of Colorado Hospital, said in a press release.

McCarter and his team examined the spleens of 26 patients with a variety of cancers, including melanoma, ovarian cancer, pancreatic cancer, and colon cancer. They found that while in mice, MDSCs are abundant and relatively easy to isolate, human MDSCs are more rare and require a complex mix of markers to be identified.

“Basically, this means that it’s really easy to find and study these splenocytes in mice and really hard to get your hands on enough human splenocytes to study,” said first author Kim Jordan, PhD, who is assistant director of the CU Cancer Center Human Immune Monitoring Shared Resource and assistant research professor at the CU School of Medicine Department of Immunology and Microbiology. “Now with this paper, we show how future researchers can isolate these human splenocytes, hopefully leading to more work in this area.”

When the team compared spleen samples from cancer patients to samples collected from patients with benign pancreatic cysts, they found that MDSCs were more abundant among cancer patients. But unlike what is seen in mice, MDSCs from both cancer and non-cancer patients were found to be immunosuppressive.

“We show that these cells are functionally immunosuppressive in humans, working to block T-cell responses,” said McCarter, adding that patients with higher MDSC counts were “associated with a significantly increased risk of death and decreased overall survival.”

Although several immunotherapies that boost T-cells, like immune checkpoint inhibitors, have shown promise in a variety of cancers, a larger number of patients still fails to respond to those therapies. Based on their findings, the researchers believe that MDSCs in the tumor may be in part responsible for resistance to immunotherapies, which led them to initiate a clinical trial assessing whether the efficacy of immunotherapies could be improved by drugs targeting MDSCs in tumors.

“Currently only about 20-40 percent of melanoma patients respond to these immune therapy checkpoint inhibitors for a variable amount of time,” said McCarter. “By blocking or knocking down the myeloid-derived suppressor cells, we hope to improve this response rate.”

The authors plan to report the results from this small trial in a forthcoming publication.