In a new study entitled “Allogeneic IgG combined with dendritic cell stimuli induce antitumour T-cell immunity” published in Nature, a newly-designed strategy by researchers at Stanford University School of Medicine shows that mouse T cells can be primed to attack and destroy cancer cells. The team’s strategy was efficient in eliminating not only primary tumors but also metastases of different cancer types. These findings carry a great potential for future applications in clinical therapies.

A major concern in the field of organ transplantation is the occurrence of organ rejection, an event mediated by the rise of antibodies – molecules that detect foreign substances in the body – targeted against the new, foreign tissue. With antibodies binding to foreign cells, they initiate a signaling cascade that culminates with the activation of certain T cells that destroy and eliminate the “foreign” tissue.

The same process of rejection occurs when transplanted tumors are inserted into new mice. However, while understanding how this process is initiated would allow researchers to mimic this response in naturally arising tumors, the mechanisms behind such a process were unknown.

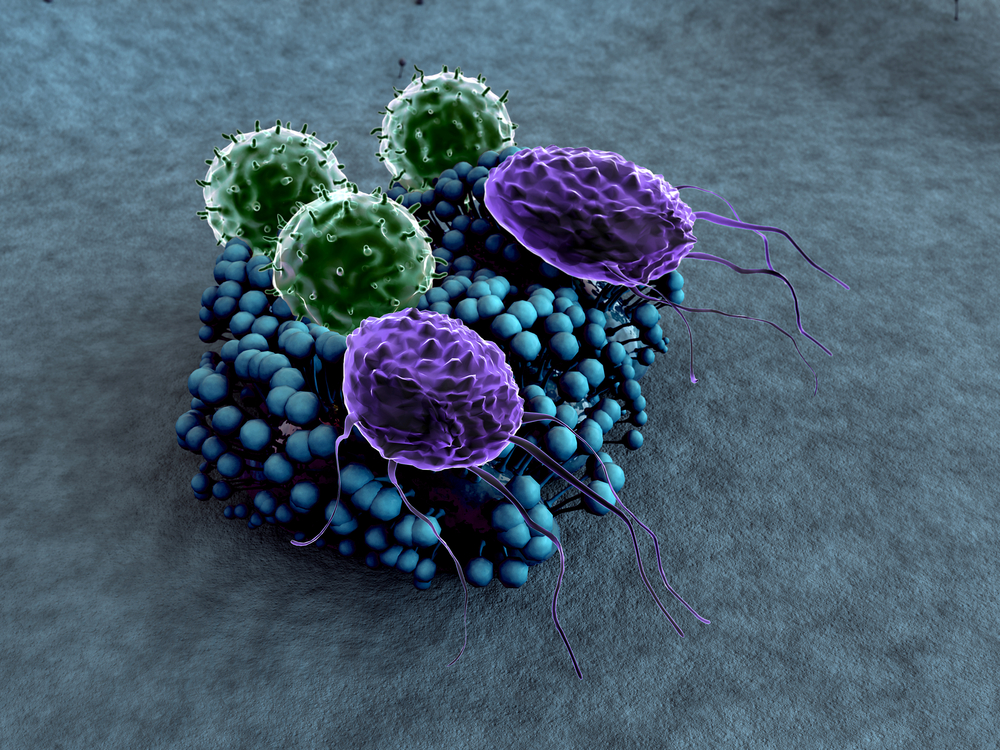

In this study, a research team led by Edgar Engleman, MD, PhD, discovered how transplanted tumors are ultimately eliminated by mouse immune system, with antibodies, T cells and dendritic cells playing the leading roles.

The team found that antibodies binding to tumor cells trigger tumor rejection and enable nearby dendritic cells to present tumor-antigens in their surface receptors. As professional antigen-presenting cells, dendritic cells present tumor-antigens to T cells that are then primed to recognize tumor tissue.

The researchers tested this mechanism as an effective way to eliminate tumors, injecting cancer cells from different tumors into mice and allowing them to grow. After two weeks, tumors were surgically removed and mixed with plasma of a cancer-free mouse, form another species, triggering the generation of antibodies directed towards the cancerous-tissue. The antibodies that were bound to the tumors, were then collected and injected, with or without dendritic cells, back into the mice. The team discovered that mice who received the combination of antibodies and dendritic cells rejected the tumors, and remained cancer free for at least one year. They found that only when injecting both antibodies with dendritic cells an effective T cell response was mounted against tumors cells.

This novel strategy was tested in different mouse models of melanoma, pancreas, lung and breast cancer, and in all an efficient T cell response occurred. Additionally, they discovered that not only does this strategy eliminate the primary tumor but is also successful in eliminating distant tumors and metastases. Importantly, the team validated their findings in human patients suffering with lung cancer.

These results demonstrate that tumor-binding antibodies can induce a potent and effective immune response that can be explored in future cancer immunotherapies.