Creating a vaccine from a type of immune cell extracted from tumors could be a promising way to treat cancer, Belgian researcher say.

There are two types of these dendritic cells, however — and they use different mechanisms to fight cancer. So scientists need to learn which of the subsets would benefit which patients.

The study, “The tumour microenvironment harbours ontogenically distinct dendritic cell populations with opposing effects on tumour immunity,” was published in Nature Communications.

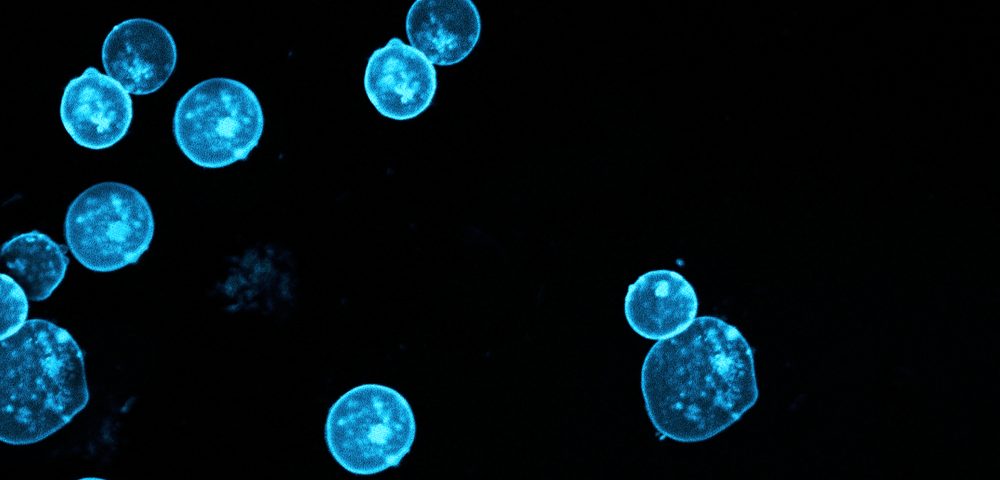

Dendritic cells are specialized immune cells that activate our immune system. Their presence in tumors has been correlated with a better patient outcome. But studies have suggested that tumors can suppress dendritic cells, blocking an effective immune response against the cancer cells.

Different subsets of dendritic cells are known to exist in healthy tissue, but whether this was the case in tumors was unknown.

Researchers from Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VIB) and the Inflammation Research Center in Ghent examined dendritic cells in tumors. They found two functionally distinct subsets in tumors in mice and humans, which they dubbed cDC1 and cDC2.

“We believe that DCs taken from tumors are well-suited for cancer immunotherapy, since they’ve been confirmed present within removed tumors and cause a strong anti-tumor response even in low numbers. The fact that we even discovered two different suitable DC types comes as a surprise,” Jo Van Ginderachter, a professor at VIB and the study’s lead author, said in a press release.

Additional analysis showed that the subsets trigger anti-tumor immune responses in different ways. CDC1s bolster tumor-killing T-cells. CDC2s fight tumor-infiltrating immunosuppressive cells, such as myeloid derived suppressor cells and anti-inflammatory macrophages.

This suggests that in tumors dominated by immunosuppressive cells, a cDC2 vaccine that triggered more powerful suppression of tumor growth would be the way to go. In tumors with low numbers of immunosuppressive cells, the best approach might be a cDC1 vaccine that prompted tumor-killing T-cells to make a direct attack.

“For this study, we performed vaccinations using the DCs that we took from actual tumors to reveal their potential. Logically, the next step will be to find out whether vaccination will be successful in a therapeutic setting,” Van Ginderachter said. “We will have to remove the tumor, isolate the DCs and then re-inject them into the same individual to discover whether we can prevent the formation of new tumors and relapse of the main tumor. These next steps are also crucial for us to better understand why some tumors respond better to cDC2 and others to cDC1 vaccination. For this part we are actively looking for a partner.”