Researchers have found that blood levels of a subset of immune cells, called CD8+ T-cells, following immunotherapy targeting the PD-1 pathway can help determine the anti-tumor response of lung cancer patients.

Their study, “Proliferation of PD-1+ CD8 T cells in peripheral blood after PD-1–targeted therapy in lung cancer patients,” appeared in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

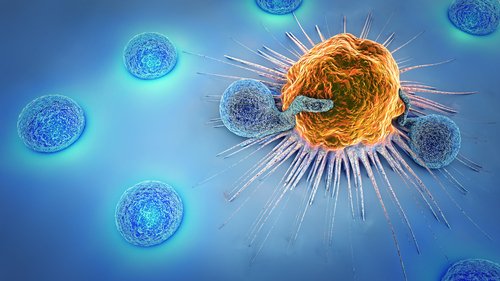

Immune CD8+ T-cells express a surface protein called PD-1 that acts like an “off’ switch when interacting with its ligand, PD-L1. This ligand is usually expressed by healthy cells in the body, acting like a white flag to prevent T-cells from attacking them.

However, cancer cells take advantage of this mechanism to evade attacks from the immune system. Cancer cells often express PD-L1, which allows them to escape the regular immune surveillance.

Drugs targeting PD-1 or its ligand, such as Keytruda (pembrolizumab), Opdivo (nivolumab), or Tecentriq (atezolizumab), are commonly used in cancer patients to reactivate CD8 T-cells, unleashing their ability to destroy cancer cells.

A team of researchers from Emory University‘s Winship Cancer Institute in Atlanta evaluated blood samples from 29 patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) undergoing immunotherapy treatment with PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitors. They collected blood samples before starting treatment and before each treatment cycle.

Researchers found that about 70 percent of patients had higher levels of CD8 T-cells in their blood after starting anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. Although this suggests the immune system was responding to treatment, only some patients showed a partial clinical response, deemed as a tumor burden reduction of at least 30 percent.

Evaluation of patients’ outcome after treatment showed that those with partial responses survived at least one year, whereas only one out of seven patients with progressive disease was alive after a year.

A detailed analysis of the CD8 T-cell pool in each patient showed that an increase in activated PD-1-positive CD8 T-cells was predictive of response to treatment. Indeed, 80 percent of patients with clinical benefit exhibited PD-1-positive T-cell response within four weeks of beginning treatment. In contrast, 70 percent of patients who did not respond to treatment showed delayed or absent PD-1-positive CD8 T-cell responses.

The authors reported that expanding CD8 T-cells were characterized by expression of high levels of PD-1, as well as other molecules that aid their activity.

“We hypothesize that re-activated CD8 T-cells first proliferate in the lymph nodes, then transition through the blood and migrate to the inflamed tissue,” Rafi Ahmed, the study’s co-senior author, said in a press release. “We believe some of the activated T cells in patients’ blood may be on their way to the tumor.”

These results suggest that an early activation of PD-1 expression in CD8 T-cells after immunotherapy treatment seems to be essential in anti-tumor response. Although not established as a prognostic tool, identifying and quantifying activated CD8 T-cells can help both physicians and patients to decide the best immunotherapy treatment strategy.

“Our ability to detect proliferating T-cells in the blood and correlate this with clinical benefit is exciting, since this captures a real-time assessment of the immune system’s response to PD-1 directed therapies and is a readily accessible test from our patients’ perspective,” said Rathi Pillai, author of the study.

The team is already developing larger studies to confirm these results, also addressing the predictive potential of CD8 T-cells in other cancer types.