A new approach using genetically modified T-cells may become the first clinically viable, targeted immunotherapy for T-cell blood cancers, a preclinical study reports.

The study, “An “off-the-shelf” fratricide-resistant CAR-T for the treatment of T cell hematologic malignancies,” was published in the journal Leukemia.

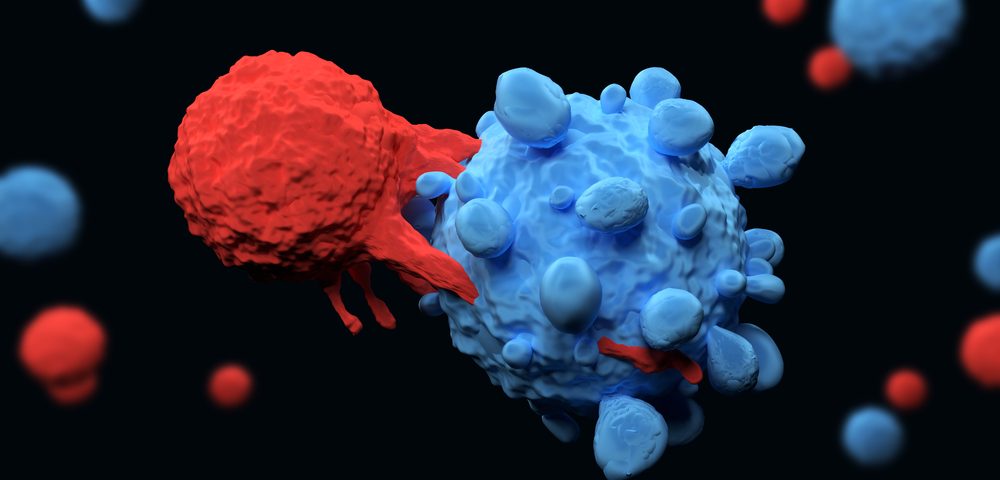

T-cells, a type of white blood cell, recognize foreign molecules through specific membrane receptors. T-cell receptors can be genetically altered to specifically recognize and kill tumor cells, a therapy called chimeric antigen receptors (CAR) T-cell therapy.

CAR T-cell therapy requires taking blood from the patient, isolating T-cells, changing the cells genetically to attack proteins associated with cancer, and then infusing them back into the patient. The most suitable target protein must be one that’s highly expressed by tumor cells and absent in healthy cells.

In T-cell lymphoma, most target surface molecules are shared between healthy and cancerous T-cells, resulting in unwanted self-elimination of CAR T-cells, or fratricide. The very process of harvesting sufficient T-cells from patients is quite inefficient, as most T-cells are cancerous.

Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine have developed a new CAR T-cell approach that produces anti-tumor T-cells that do not attack themselves, and that does not require a patient’s own T-cells.

Researchers designed the T-cells to target a surface protein called CD7, which is highly produced by cancerous T-cells. Since CD7 is also present in healthy T-cells, it was genetically removed from CAR T-cells, avoiding self-elimination.

This was achieved with the CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing system, which is similar to editing system used by bacteria as a defense mechanism, allowing researchers to edit parts of the genome by adding, removing, or changing specific sections of the DNA.

To create CAR T-cells from any donor, without the possibility of them viewing the recipient’s body as foreign and reacting against it — a condition called graft-versus-host disease — their T-cell receptor was also removed with the CRISPR/Cas9 system.

This new approach, called fratricide-resistant “off-the-shelf” CAR-T (or UCART7) was found to be effective against human T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) in the lab and in a mice model.

Mice treated with UCART7 survived more than twice as long as mice treated with CAR-T cells targeting a different protein, or untreated mice. The UCART7 T-cells were still present in the blood of mice after at least six weeks, suggesting that they might also prevent relapses. No evidence of graft-versus-host disease was found in these mice.

“One additional benefit of this approach is that … we wouldn’t need to harvest the patient’s own T-cells and then modify them, which takes time,” Matthew L. Cooper, PhD and the study’s first author, said in a press release. “We also wouldn’t have to find a matched donor. We could collect T-cells from any healthy donor and have the gene-edited T-cells ready in advance.”

Researchers believe this strategy may represent the first clinically viable targeted therapy for T-cell blood cancers, such as relapsed T-ALL and non-Hodgkin’s T-cell lymphoma. They are currently working on improving and scaling up production of these CAR T-cells to move to clinical trials.